Mario Kart’s biggest draw isn’t its slick and speedy gameplay, its colorful cast with more colorful maps, or its popularization of the karting genre in 1992’s Super Mario Kart. What really sets Mario Kart apart from its racing competitors is just how goddamn accessible it is.

In comparison to huge franchises like Call of Duty, Halo, or Uncharted, Mario Kart outsells its competition by a wide margin. The newest edition to the series, Mario Kart 8 Deluxe, has sold more copies to date than any other Nintendo Switch title thus far: 19 million. That’s more than any other Zelda, Pokémon, or Mario game, all of which I assumed had far more pull than Nintendo’s Mario Kart. Not only is Mario Kart 8 Deluxe sitting financially above its pixelated bedfellows, but also no game on the Xbox One or Playstation 4 has sold more than Mario Kart 8 Deluxe. Let me say that one more time - no game on any one console in this generation of console gaming has sold more than Mario Kart 8 Deluxe. Of course, Nintendo maintains an exclusivity that avoids multi-platform releases, but the fact remains that Mario Kart is a force to be reckoned with.

Yet the game’s accessibility and accompanying popularity doesn’t stem from ‘Mickey Mouse’ difficulty, but the game’s allocation of power-ups based on your position in the race - the worse your position in the race, the better your odds are of getting a better power-up. Success isn’t predicated on luck or skill, but rather a combination of the two.

This isn’t to say that games classified as ‘accessible’ are better than games with Dark Souls’ difficulty, DOTA 2’s steep learning curve, or masocore’s invitation to die thousands of times (I died over 4,000 times before beating Celeste). A game like Mario Party is always going to be about sociability and casual interaction while any Zelda iteration regards skill and accomplishment as its motivating factors. Meanwhile, Mario Kart is regarded as a touchstone for the video game canon because its balance between serious mechanics and playful settings are perfect for mid-game commentary - the kind consisting of vengeful threats, impish taunts, and hubristic boasts. Nintendo’s developers include features that make the game not easier but more approachable, with multiple feature that acquaint new-comers with its mechanics. For example, “smart steering” keeps you on the racecourse and protects you from falling off, while tilt-sensing controls feel more logical for non-gamers that understand how a steering wheel works. Mario Kart’s minimalist controls make drifting pretty forgiving, so forgiving that you don’t even need to hold down the “A” button to accelerate - your car will drive automatically. But among Mario Kart’s draws for novices is its hallmark of inventive power-ups that make the game radically more playable regardless of your skillset.

For the uninitiated, a power-up is a floating box that appears a handful of times on the track that when driven into gives your avatar a particular ability you can use only once. A typical power-up might be a mushroom that gives you a speed boost or a bomb that you toss incapacitating other players for a few seconds. At first glance, it seems a power-up is as randomly generated as any other player, but the reality is anything but random. For example, a racer leading the pack will only get mediocre power-ups like the banana peel or the green shell. Shells, a power-up essential to understanding what makes Mario Kart special, are carapaces that caroom towards a player, knocking them out for a few brief seconds so that other racers can zoom ahead. A green shell must be aimed and requires some skill, and it’s one of only three power-ups provided for the front-runner, the others being a banana peel that players from behind may slip on, and coins which make you go a tiny bit faster. As you can imagine, this shell doesn’t do much for someone in front of other racers and none of the power-ups that are provided for front-runners contribute to cementing their lead. The red shell has the benefit of locking onto the racer right in front of you even if they’re leagues ahead, making it greatly desirable for any player wanting to scoot forward one place. These shells, however, can be intercepted by obstacles on the racetrack or be dodged by more dexterous racers. But the granddaddy of them all is the blue shell or spiny shell, a weapon accessible to only the biggest losers. This weapon not only locks onto the first-place racer, but knocks him out for a few seconds - no matter what. The blue shell is the bane of winners and ensures that even the best players have to look out for the specter of the blue shell as it’s lobbed forth - ironically - by the most “unskilled” (or unlucky) of players.

Power-ups facilitate newbies and underdogs alike to stay in the game depending on your position on the track. This biased distribution isn’t actually explained to the player, which means players at the back can simply feel lucky rather than know there’s a bit of hand-holding going on. Instead of ability governing the winners and losers, chance comes into play just enough that if you lose, you can’t really beat yourself up about it, but if you win, you can certainly chalk it up to skill. This has enormous implications for accessibility in games - unlike most games where chance has no or minimal impact on the game, Mario Kart balances performance through this calculated amalgam of skill and chance. It’s serious enough that practice improves your game but playful enough that a seven-year-old newly introduced to the game can best even the most seasoned player. The endorphin release developing-players get through this distribution of power-ups incentivizes greenhorns to win and feel like survivors of the Battle of Normandy when they might have just gotten a lucky break. Operation Overlord indeed.

Effectively, power-ups like the blue shell even the playing field. They intervene to ensure amateurish players want to participate, improving their game through this weaponized scaffolding. Inversely, veterans are made to feel unsure of their lofty placement, keener to master a course than phone in their win. Some power-ups doled out to the bottom half of the totem pole are Bullet Bill (a power-up that transforms someone in last place into an indomitable bullet that races ahead), the Golden Mushroom (allowing you to accelerate at will for a duration much longer than other power-ups), and the Star (making you invincible and faster for a healthy duration of time). None of these give an unfair advantage to tail-end racers. Instead, these power-ups promote competition between racers, encouraging participation and generating suspense. The down-and-out are neither down nor out.

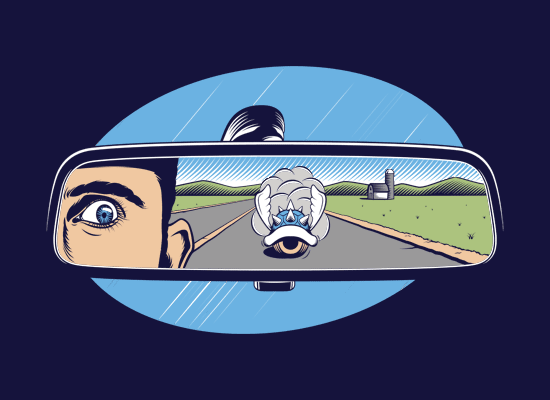

It’s this direct confrontation between the last and first with the use of the blue shell that contrasts with capitalism’s engrained assumption that economic “winners” are insulated from economic “losers.” We get to see our lived class stratification usurped in Mario Kart.

When I first felt the urge to write on the unexpected parallels between Mario Kart and capitalism’s class interplay, I was disappointed (and encouraged) when I found theorist Ian Bogost had similarly tackled this same issue in his ironically titled essay “The Blue Shell is Everything That’s Wrong with America.” His analysis of Mario Kart 64’s inclusion of the blue shell assessed how the blue shell’s evolving function in successive Mario Kart games represented how games echoed geopolitical currents. The U.S.’s increased globalism and economic downturns in the 21st century contrast with the somewhat golden age of the 90s, the decade bookended by the end of the Cold War and the onset of the War on Terror - the same decade of Mario Kart’s birth. Originally, the blue shell could be dodged on the Nintendo 64 and sidestepped on the Gamecube. Competition in Mario Kart had shifted from true racing to the blue shell’s mollycoddling for those left behind, citing 9/11, War in the Middle East, and the 2007-2008 Recession as events that fueled the escapism of the downtrodden in the first decade of the century. As he sardonically implies, new Mario Kart games make it so anyone can win:

“The Blue Shell steals progress from a rightfully earned win on behalf of the lazy and incompetent. The Blue Shell wrests spoils from leaders’ fingers just as thy reach for the laurel. The Blue Shell is the cruel tax of gaming, the welfare queen of kart racing. God damn you kids today. We used to have to win a race to win it.”

Sarcastic and cheeky yes, but Bogost’s overall point isn’t that serious, and if he’s critiquing anything it’s a pathologizing of video games as a refugee for the weak. Mario Kart: an inversion of societal truths where losers win and the winners lose. And to a certain extent he has a point when he writes, “Today, winner and loser alike know that the real winners aren’t even in the game, aren’t even on the course. Real winners need not even bother with Mario Kart, for they have managed to master a real Blue Shell in the interim, a trump card against the universe.” What will often happen with the hurl of a blue shell isn’t necessarily the thrower defeating the throwee. Often, the second-place racer will win, arbitrarily dictating the win. The blue shell throws the whole balance of the race into disarray, anarchy, and discord - pure freaking bedlam. An article for Wired makes this very claim, associating the blue shell with Kierkegaardian ressentiment, the wretched of the Earth spiting the victorious not out of justice but malice.

Yet in a game about plumbers, princesses, and turtles racing on rainbows and canyons literally made out of candy, the blue shell doesn’t punish winners so much as elevate losers - something capitalism could take a lesson from. Whether a specific analogue to the blue shell is best represented by a wealth tax, welfare, or affirmative action is inconsequential. What it comes down to is a top-down interventionism that boosts participation in the structure at large. If life imitates art as Oscar Wilde once opined, then maybe world leaders should pony up $60 and get themselves a copy of the game. As in both Mario Kart and capitalism, winners and losers will always exist - what can be different is how today’s losers can be tomorrow’s winners.

If both Mario Kart and capitalism work so well because of the balanced role interventionism plays within these competitive spheres, an appropriate analogy can be identified in the theories of 20th-century economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynesian economics do not tout laissez faire competition but the necessity of governmental interventionism to correct a system supposedly guided by an invisible hand. Adam Smith’s theory of capitalism’s invisible hand claims that the system supports itself naturally, supposing that occasional government oversight is necessary in times of privation or devalued currency, but that capitalism can and should regulate itself as if its processes were as natural as the birds and the bees. Before Keynes, it was believed that disrupting the flow of capitalism with stimulus packages, work relief programs and tax cuts would interrupt the dynamic between consumption and production. This is like saying rivers don’t flood, they just get higher than normal sometimes, suggesting the attempt to stymie such natural processes is ignorantly futile. But rivers do flood, and it’s up to the state to step in and shore up a community’s defenses to prevent this from happening.

The comparison between Mario Kart and Keynes suggests that the operation of an accessible gaming model requires top-down regulation and influence that elucidates how improving a system requires undoing the false fairness of neutral treatment of all players. Before Keynes, macroeconomics could be defined under one law - Say’s Law. Say’s Law is simple: “Supply makes its own demands.” Say’s Law presupposes that the market eventually absorbs what it puts out, meaning that while the market may occasionally rock back and forth in bull and bear markets, it will never be so imbalanced that any institution will need to step in. The problem as John Maynard Keynes saw it, was that this simplification of capitalism as self-regulatory fails to take into account the hoarding of wealth where the market does not absorb what it puts out because it remains firmly in the hands of plutocrats who don’t reinvest their capital. Say’s Law also fails to account for the economic disasters during capitalism’s three ongoing centuries of dominance. Panics, recessions, and depression all took a devastating toll on human lives, which lead up to capitalism’s catastrophic masterpiece, The Great Depression, which Keynes’ directly responded to. Unlike the necessary regrowth a destructive forest fires brings, capitalism doesn’t require the leveling force of an economic disaster to stay healthy. In The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes explicates how unemployment and inequity could be curbed through public works and initiatives at the federal level. Contrasting with capitalism, this created jobs and filled gaps free markets did not account for during the Depression. This interventionism greatly decreased unemployment and encouraged job creation because profits made by companies were withheld when they were theoretically supposed to go back into the market for job creation.

A singular solution like welfare might assuage poverty but the metaphor of Keynesian economics operates with the understanding that a fair solution must be systemic rather than palliative. Without the “uneven” distribution of power-ups in Mario Kart, where lesser players get better power-ups, it would be just another racing game where the law of the jungle prevails: might makes right. Mario Kart’s egalitarian model competes with first-person shooters that follow a highly competitive model in which a player with the highest kill count gets benefits that intensifies their killing spree (collecting more weapons, finding better spots, hording power-ups). Instead, Mario Kart’s negative-feedback loop for winners that prey on the weak is a necessity, both in video games and economics. The false narrative of a self-regulating or neutral market is just as spurious as a video game without the negative-feedback loop that successful players have to go through lest they tip the scales of the game into all-out slaughter.

Of course, progressive taxes accomplish the same thing Mario Kart does; both take more from those on the top than those on the bottom. I found this too obvious and rather uncomplicated and instead wanted to emphasize a dominant and hackneyed faith in free markets - that a neutral playing field is a fair playing field. When the increasing inequity between the top and the bottom becomes egregious, a trend all too familiar with anyone reading the annual data corroborating such patterns, it’s Keynesian economics that restructure the rules of the game. Evidence like this is the writing on the wall - markets cannot frame themselves as neutral. Democratically elected leadership needs to pull in the reins and undo the narrative of a facile neutrality those on top defend. Equal treatment of the rich and poor or winners and losers is never equal; it widens the distance between the top and bottom until nobody wants to play at all.

The analogy of Keynesian economics is this: the unfettered processes of capitalism or a race eventually result in inequity, privileging those best equipped to subvert it for their own pleasure. When you think about the blue shell, think of it as introducing more players to the thrill of leading the chase, letting players exercise skills free from the bombardment of being bunched up with the pack, giving access to a lead that motivates future attempts. If capitalism is supposed to be a meritocracy (which is questionable), Mario Kart uses its power-up distribution to test the lucky and galvanize the unlucky. Imagine what Mario Kart would be like for players if power-ups were evenly distributed. Players with more experience would get better power-ups that solidified their win, while a player in the rear would be more reliant on luck than ever. If you want anything to be a true meritocracy, that means identifying that it’s not a merit to be born with merits. True meritocratic capitalism would strip benefits like inheritance and outlaw the inevitability of plutocracy in free market capitalism. In fact, both of these points are elements of a real-life Meritocratic Party.

The comparison between Mario Kart’s power-up distribution and Keynesian economics may be a stretch. An average citizen’s participation within capitalism isn’t about winning so much as it is about getting by, while video game competition always seeks out besting a small pool of temporary players. Yet the fact remains that both of these competitive structures aren’t supposed to be about competing for the sake of competing: they’re about enjoyment. Video games and capitalism can have competition (it’s essential to capitalism), but if they are about feeling joy, fulfillment, or the pleasure of work, what better way than to encourage a system where those on the bottom are actively rewarded to put pressure on those on the top. Vice versa, players used to winning have to step up their game and never assume their victory is assured. If a winner is someone who’s hard working, then what better way to prove one’s merit than by overcoming the handicap of the dreaded blue shell as it empowers a proletariat swooping up your flanks!

As great as Keynes or Mario Kart appear within capitalism and gaming, neither are as idealistic as I’d like. They’re both better at improving systems that are pretty flawed from the get-go. When first delineating what this essay would be about, I wanted to compare Mario Kart to communism or at least socialism, economic models that privileged inclusivity, equity, and community. But Mario Kart is unequivocally capitalistic! The import of competition, the cartoonish aggression amidst a race, the aggregation of coins that makes you accelerate depending on the number you have - all of these complement Japan’s hyper-capitalism and America’s maddog materialism at any cost. But power-ups allow us to work with what we have. They aren’t “handouts,” but incentives to participate and reduce inequity, making the game a much fairer version of competition than the myth of the free market. The predictability of winners may decrease but so does the predictability of losers. What becomes emphasized in the end is the joy of racing with friends more than the domination of lesser players. My own experiences playing Mario Kart with noviates and alpha geeks alike resulted in being unexpectedly beat and unexpectedly victorious. Gameplay with friends wasn’t just about being the best as it was indulging in yelps and shrieks as I tossed a bomb into a gaggle of karting avatars or discovering a secret passage that cut my lap time by a few seconds. Unavoidably, winning is always on your mind, but a game about winning doesn’t have to be cutthroat. Instead, capitalism, much like Mario Kart, should realize that what makes it attractive isn’t making the great greater but having there be more greatness to go around - even if it means you sometimes have to lose.

Want more Mindless Pleasures??? Delve into the full catalog of entries here.

Jordan Finn lives and works between Billings, MT and Brooklyn, NY having just competed his M.A. in English and is figuring out how to avoid a real job. He spends his time writing short fiction and essays, playing drums for a number of bands, and reading the works of Philip Roth. He also has a love-hate relationship with video games and television that he’s working out.